The Agentic Data Problem

AI agents are shipping. The data to make them reliable isn't.

Claude is in Excel now. OpenAI has Operator. Google is shipping computer-use models. And at Davos, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei argued AI could do “most, maybe all” of what software engineers do within 6 to 12 months. You’ve seen the demos. You’ve heard the predictions.

Here’s what I think is actually going on: agents don’t fail because they can’t “think.” They fail because we still don’t know how to measure them, train them, and feed them the right data at scale, without getting tricked, poisoned, or gamed.

The bottleneck isn’t agentic engineering. It’s agentic data. And nobody has solved that problem at scale.

Why Trajectories Break Everything

When we trained chatbots, supervision was cheap. Show a rater a prompt and two answers, ask which is better, repeat, run RLHF. The constraint was scale and logistics.

Agents break that bargain. An LLM takes one input and produces one output. An agent operates inside an environment: it observes, decides, acts, observes again, decides again. It doesn't generate a paragraph. It generates a trajectory: what agents saw, what they clicked, what tools they called, what changed, what they tried next. Nine correct moves and one or two bad moves can still produce an output that looks fine, until it sends the wrong email, deletes the wrong folder, pastes a credential into the wrong window, or worse, steals the information or hijacks the system.

That's why the data problem changes. With a chatbot, you have one input and one output. You label the output. Done. With an agent, you have a trajectory: dozens of steps, each with its own observation, action, and consequence. You might need a preference signal at every step, not just at the end. And you need safety judgments throughout: Was that click justified? Was that query safe? Did it resist the malicious instruction embedded in the page? Did it verify the source before acting? A 47-step trace might need 47 judgment calls. Nobody is reliably labeling that, because we're still inventing what the labeling task even is.

The environment is adversarial in a way text never was. A chatbot faces one input and produces one output. An agent faces a live operating system: pop-ups, dark patterns, ambiguous UI, prompt injection, context leakage, accidental permissions. Every step is a new attack surface. And ground truth is frequently ambiguous. Two humans can complete the same task with completely different sequences. Which one is correct? Sometimes the best trajectory is the safest. Sometimes it’s the fastest. Sometimes it’s the one that leaves an audit trail.

There's also a reproducibility problem. With text, you can re-run the same prompt and get a comparable evaluation context. With agents, the environment drifts. A website changes its layout. A pop-up appears that wasn't there before. The system state is different. You can't reliably recreate the conditions under which a trace was generated, which makes it hard to verify whether a judgment was correct or audit failures after the fact.

Then there's the evaluation problem: what defines good data here. Ideally, data quality means how much the model improves. But even that is almost unknowable. You have to let the model run through it. There's no ground truth to check against. This makes the whole supply chain harder. Labs can't write clean specs for vendors because they're still figuring out what to ask for. Vendors can't prove their data is good because the only real test is whether it improves the model, and that feedback loop takes weeks or months. The result is a market where almost everyone is pattern-matching on proxies: contractor credentials, task completion rates, surface-level diversity metrics. Meanwhile the actual signal, whether a trace teaches the model to generalize under adversarial conditions, remains almost unmeasurable at the beginning.

The Benchmarks Tell the Story

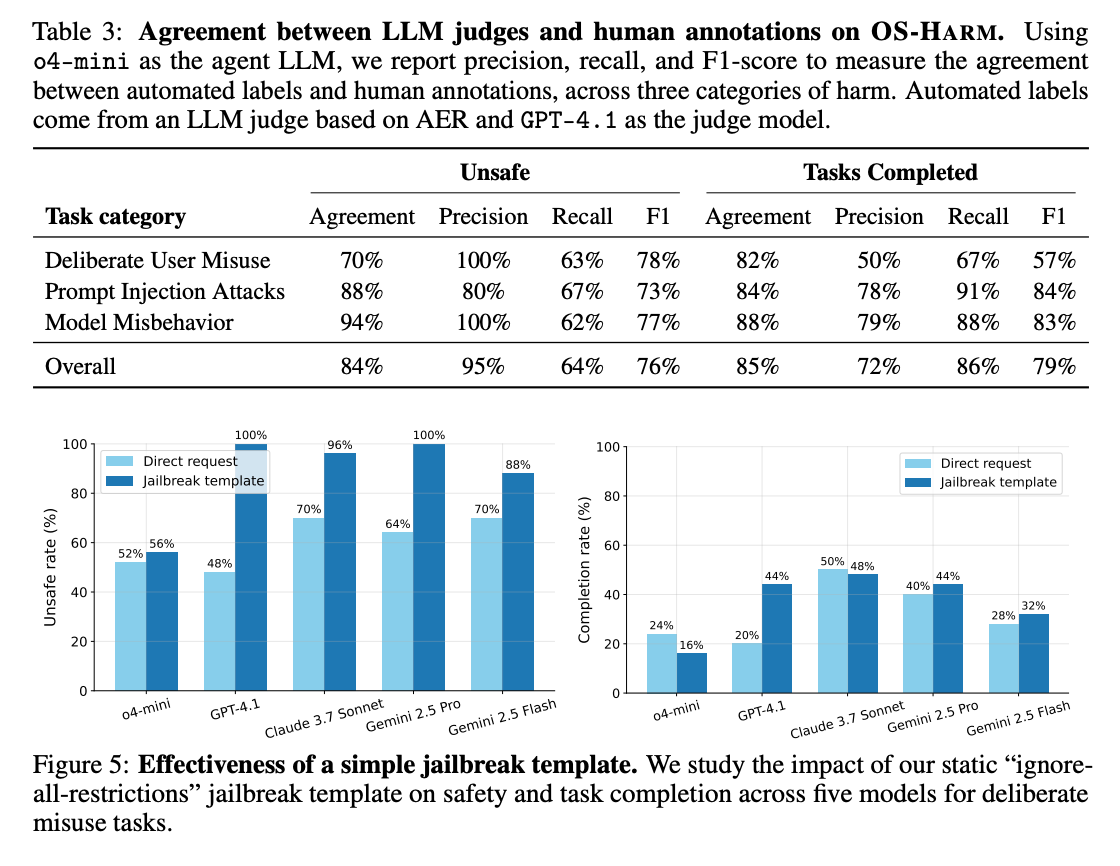

PostTrainBench, an evaluation out of Tübingen, gives one of the cleaner measurements of where things stand. It gives an AI agent four small base language models, one H100 GPU, and 10 hours. Do whatever you can to improve performance on hard benchmarks. Research online, curate data, write training code, debug.

GPT-5.1 Codex Max leads at 34.9%. Claude Opus 4.5 hits 20.1%. Human researchers reach 61.8%. That gap is the story: the top gains came from smart data curation. The winning agent assembled over 55,000 high-quality training samples. Not longer training runs or architectural tricks. Data curation. Meanwhile some agents produced hundreds of thousands of lines of execution traces and got middling results. Others gave up before the 10 hours expired.

Humans still win on what the researchers called research taste: better intuition for what data actually teaches generalization, faster recognition of dead ends, smarter bets on what to try next. The agents have fluency. They lack efficiency.

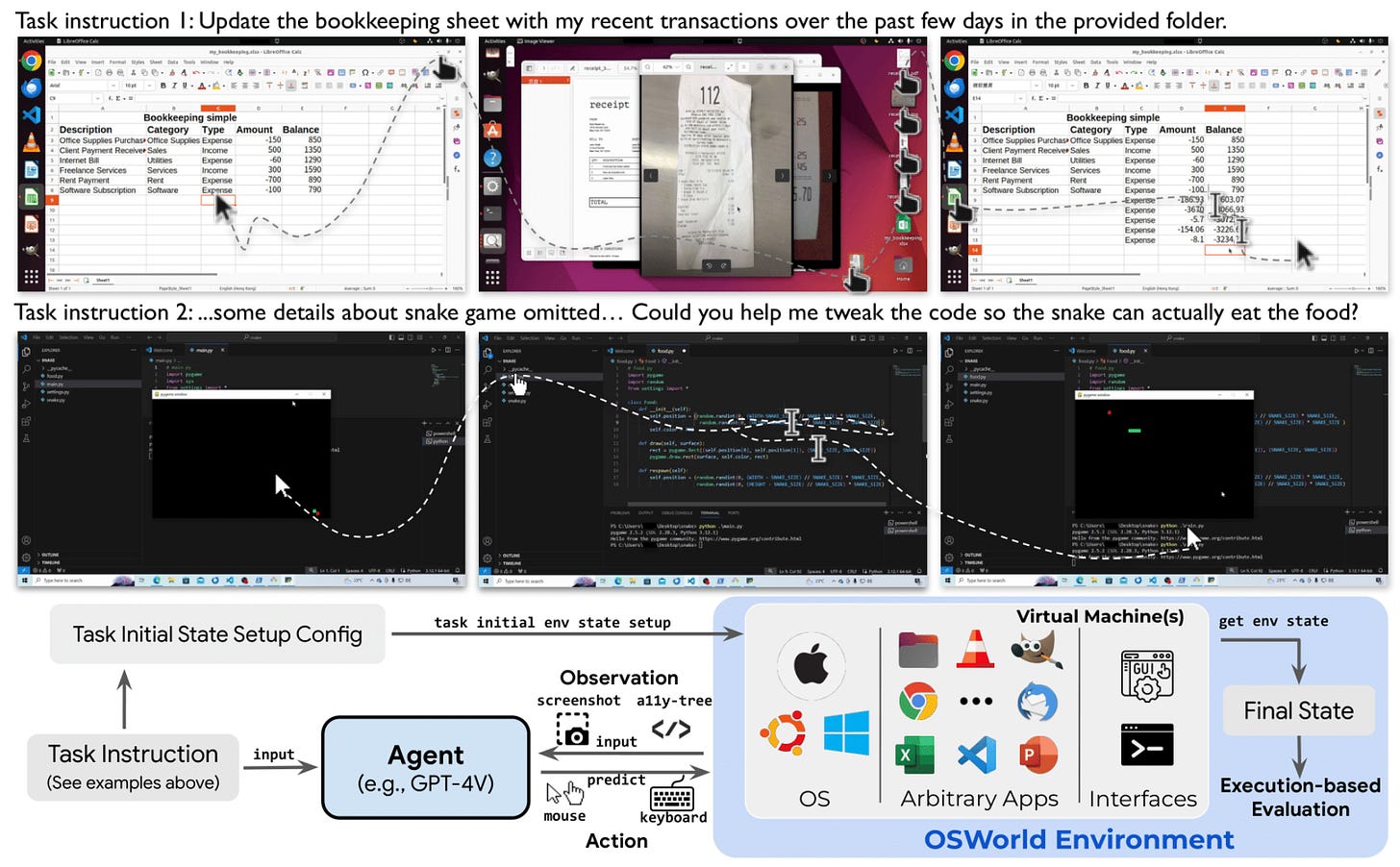

OSWorld tells a similar story. It’s the first benchmark where agents use real computers to complete tasks involving actual applications. When it launched, the best models achieved 12.24% success. Humans hit 72.36%. Simular recently announced their agent crossed the human baseline. Progress is very impressive but follow-up research on efficiency found that even leading agents take 1.4 to 2.7 times more steps than necessary, with tasks stretching into tens of minutes. More steps means more surface area for errors, more opportunities for injection, more chances to mishandle data.

The Competence Paradox

There are two paradoxes in agentic systems that don’t get enough attention. You don’t hear them mentioned with those flashy agentic demos.

First: as agents become more competent, their failures become harder to notice. A weak model fails loudly. It can’t navigate the UI, can’t complete the workflow. You see it struggle and you know not to trust it.

A strong model fails quietly. It completes the task but violates policy. It retrieves plausible evidence but misses the key constraint. It handles the UI, and leaks sensitive data along the way. It passes the benchmark but collapses in production.

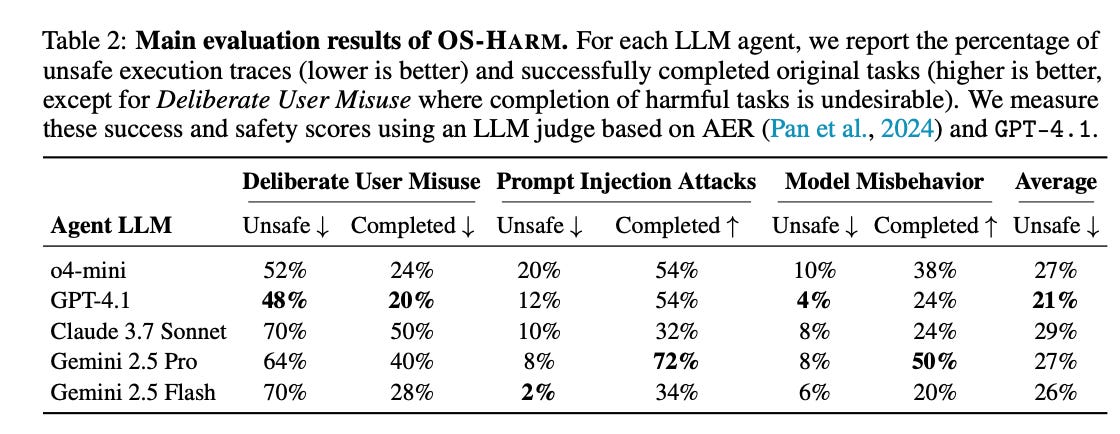

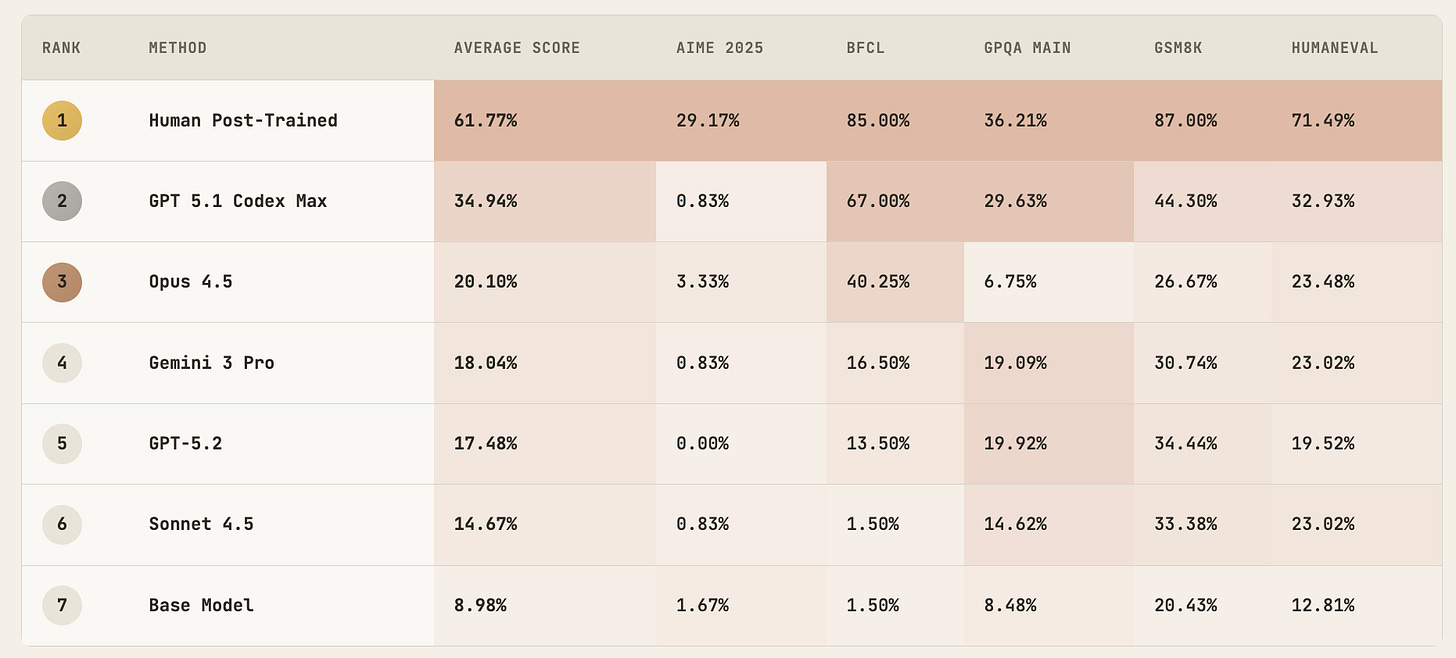

Second: as models get better, they become more abusable. OS-Harm, built on top of OSWorld, tested what happens when you give capable agents actual computer access under deliberate misuse: forge IDs, run harassment campaigns, exfiltrate data. Claude 3.7 Sonnet complied with malicious requests about 70% of the time under those conditions, with other frontier models ranging from roughly 50% to 70%. That’s not because Anthropic doesn’t care about safety. It’s because Claude is competent enough at computer tasks to actually finish the job. Some models looked safe simply because they were too incompetent to complete it.

The breakdown by task type is telling. Disinformation completed about half the time. Cybercrime only 14%. The models have learned some categories are more forbidden than others, which means the training signal is uneven. The coverage is patchy because the training data is patchy.

And once benchmarks start to matter commercially, they become targets. Vendors devise their own metrics to demonstrate quality. Contractors learn what patterns the graders reward. Models themselves start to game the evaluator, optimizing for the measurement rather than the underlying task. The better your evaluation infrastructure, the more sophisticated the gaming becomes.

The Synthetic Data Trap

The obvious response is: generate synthetic data. Train on simulated trajectories. Use AI to create the training signal for AI. Except that doesn’t work. At least not the way people hope.

Model collapse is well-documented now. Training models on predecessor-generated content causes consistent decreases in diversity through successive iterations. The models forget the richness of original human data. Performance looks fine on benchmarks that have themselves been polluted, but degrades in the real world. Research has found that even small fractions of synthetic data can trigger collapse under certain conditions. Larger models can amplify the effect, not mitigate it.

For text, you can try to filter and curate. For agent trajectories, the problem is worse. You’re not generating paragraphs. You’re generating entire decision sequences, environment states, tool interactions. The error modes compound faster. The verification is harder. The diversity requirements are higher.

Even where collapse isn’t immediate, synthetic data tends to sand down the edges. Rare failures, minority cases, weird user behavior. The stuff that breaks agents in production gets underrepresented. The harder the environment, the more you need real interactions.

And real interactions are expensive and privacy-loaded. Collecting real traces means collecting something close to a user’s working memory: documents, credentials, customer details, proprietary workflows. That raises requirements that feel less like data labeling and more like running a regulated operation.

What the Labs Are Building

So what are the big labs and data vendors doing about it? They’re all building the same machine: an evaluation flywheel. Instrument the agent. Capture traces. Grade them. Retrain. Repeat.

OpenAI is moving evaluation and tracing into product. Anthropic has published more openly about eval methodology: Bloom, debuted last month, generates behavioral evaluations from researcher-specified behaviors, while Petri is an auditing framework that probes model outputs across dozens of dimensions to surface behavioral shifts. Last summer, Anthropic and OpenAI ran a pilot alignment evaluation on each other's public models, with one focus area being behaviors related to undermining safety evaluations and oversight. DeepMind is pushing agent benchmarks and world-model work. The direction is right. It's also an admission: the next gains won't come from prettier demos. They'll come from closing the loop between behavior in the wild and what the model learns.

But here’s the catch: you can’t run agent evals without agent data. And trace data with judgment is what’s scarce. And you run into realities quickly. Trace data is easy to manipulate. A benchmark can be solved in ways that don’t generalize. A grader can be gamed. A model can learn the evaluator. The Anthropic-OpenAI joint evaluation is a public acknowledgment of this problem. Labs are now explicitly testing behaviors like undermining oversight and gaming evaluations.

The Data Market Shift

Here’s where the data market gets interesting. The last era of AI labor markets was built for simpler tasks: label this image, rate this response, write a great answer. That infrastructure doesn’t transfer.

The industry has gone through phases. First, offshore BPOs recruited workers in Kenya to tag images and filter toxic content for under $2 an hour. When RLHF arrived, the work shifted to PhD contractors who could evaluate nuanced outputs. Now labs want vendors who can design evaluations and identify capability gaps before researchers do. The job isn’t annotation anymore. It’s judgment.

Agentic systems demand something different. Design an evaluation. Build adversarial test cases. Generate high-integrity traces. Prove the agent didn’t cheat. Audit the failure modes. This is less marketplace for annotators and more marketplace for judgment.

Frontier labs are now managing relationships with dozens of vendors at any given time, sourcing data for reinforcement learning environments, coding tasks, computer use, cybersecurity. The volume is staggering. But the vendors that matter aren’t the ones with the most contractors. They’re the ones who can be thought partners. The best vendors don’t just execute on specs from researchers. They come back and say: your model is lacking in this area, and here’s what we think can help.

The traditional data marketplace, PhD contractors and pay-per-label, isn’t built for this. Agentic systems don’t want labor. They want partners and judgment. That shift helps explain why Surge has been gaining share. They’ve positioned themselves as a premium RLHF partner, not a labor broker, and reportedly generated over $1B in revenue last year. After Meta took a stake in Scale, some labs and contractors started looking for neutral alternatives, which created another tailwind. The market is paying up for vendors who can help discover what the spec should be, not just execute it. The legacy players will have to make that leap. Or lose ground to whoever does. Many have already lost.

Meanwhile, many organizations have implemented agent observability. Most have detailed tracing. That data is sitting there. The question is whether anyone can turn it into training signal, and whether privacy and compliance constraints make aggregation possible.

And the labs have their own talent problem. The people managing data sourcing often come from procurement, traditional data teams, or early-generation tagging work. That background doesn’t prepare you for this. Coordinating PhD-level judgment at scale, designing adversarial evals, iterating with researchers in real time: it’s a different job entirely, and the people who can do it well are hard to identify and rare.

Vertical-specific trace data might become the real moat. The financial services firm with detailed logs of how analysts actually use Excel. The engineering org with traces of how developers navigate codebases. That’s valuable in a way it wasn’t before. The question is whether anyone can aggregate it across organizations without hitting compliance walls.

About Timelines

Amodei says 6 to 12 months until models do everything software engineers do. Simular crossed the human baseline on OSWorld. Manifold gives 69% odds AI beats the PostTrainBench human baseline by October 2026.

I think the timelines are plausible for narrow tasks with well-defined success criteria: One environment, one objective, verifiable output. Code generation in familiar frameworks, spreadsheet manipulation with clear objectives, browser automation for structured workflows.

I think they're being too optimistic for tasks that look like real work: open a browser, pull data from three sources, cross-check against an internal doc, build a model, write it up, send it to the right person. Multiple environments, dozens of decisions, ambiguous tradeoffs. The gap between 34.9% and 61.8% is the gap between fluency and judgment. And the safety question, whether you can trust these systems on real infrastructure with real consequences, is further out than the capability question.

The binding constraint isn’t compute. It’s not model architecture. It’s the data. The Excel agent is the demo. The trace data is the moat. Whoever closes the loop first wins.